Whilst carrying out research into families with relatives in our churchyard I came across Francis Davenport and his family. They are not to be found in our churchyard but their story is worth telling. (NB this is not meant to be a scholarly article!)

Francis was born probably in Lancashire but later moved to Whittington. He married Alice Quicksall in Ault Hucknall in August 1671, Sadly Alice died in 1678. The same year though he married Sarah Browne, Francis and Sarah were practising Quakers and they were married in the Friends Meeting House in Leicester. At the time being a non conformist (not accepting the requirement to attend Church of England services) was a serious matter.

Given Francis’s story and the role that Whittington was going to play in the future of the Country’s relationship with the Church of England it is perhaps worth looking briefly at how we came to this point.

We have to go back to Henry VIII and his efforts to have his first marriage to Catherine of Aragon annulled. Pope Clement VII refused the request which led Henry to initiate the English Reformation, separating the Church of England from papal authority. In 1534, Henry appointed himself the Supreme Head of the Church of England and dissolved convents and monasteries, this led to him being excommunicated by the Pope. Henry called on his Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer to drive forward the reformation.

Cranmer set out to move away from the traditions of Roman Catholicism including the saying of mass in Latin and develop a set of Anglican rules and order of services in English. Cranmer carried on his work following the death of Henry VIII and during the reign of Edward VI. This led to the 1549 Book of Common Prayer.

On the death of Edward VI the Catholic Mary I took the throne in 1553. She had Cranmer firstly imprisoned and then killed for treason and heresy. She reached an agreement with the Pope to bring Catholicism back to England. However on her death in 1558 her half sister Elizabeth I ascended to the throne. Elizabeth worked to re-establish the Church of England as separate from the Roman Catholic Church. At a meeting of senior clerics in 1563 the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion were agreed.

Elizabeth was followed by James VI of Scotland and James I of England in 1603. Attempts to persuade James to revert to the oversight of the Pope were ignored and led to an attempt by Guy Fawkes to blow up Parliament in 1605. This only strengthened James’s resolve. In 1604 a conference was held to discuss the variance of the preachings of the bible as a result a new translation and compilation of approved books of the Bible was commissioned to resolve discrepancies among different translations then being used. The Authorised King James Version, as it came to be known, was completed in 1611. It is still in widespread use.

James was succeeded by Charles I in 1625 when reformation of the church was again in debate. In 1633 together with the Archbishop of Canterbury they initiated a series of reforms to promote religious uniformity by restricting non-conformist preachers, insisting the liturgy be celebrated as prescribed by the Book of Common Prayer.

Following the execution of Charles I his son Charles II took over the Crown in 1660. One of his first acts was to implement four penal laws collectively known as Clarendon Code are named after Charles II’s chief minister Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon,

These included:

- the Corporation Act (1661) required all municipal officials to take Anglican communion, and formally reject the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643. The effect of this act was to exclude nonconformists from public office. While the legislation was not rescinded until 1828, the legal power to enforce it lapsed in 1663, and therefore many evicted officials were able to regain their positions after a few years.

- the Act of Uniformity (1662) made use of the revised Book of Common Prayer compulsory in religious service. Over two thousand clergy refused to comply and so were forced to resign their livings (the Great Ejection). The provisions of the act were modified by the Act of Uniformity Amendment Act, of 1872.

- the Conventicle Act (1664) forbade conventicles (a meeting for unauthorized worship) of more than five people who were not members of the same household. The purpose was to prevent dissenting religious groups from meeting.

- the Five Mile Act (1665) forbade nonconformist ministers from coming within five miles of incorporated towns or the place of their former livings. They were also forbidden to teach in schools. Most of the Act’s effects were repealed by 1689, but it was not formally abolished until 1812.

The 1662 Book of Common Prayer was the authorised liturgical book of the Church of England and other Anglican bodies around the world. In continuous print and regular use for over 360 years, the 1662 prayer book is the basis for numerous other editions of the Book of Common Prayer and other liturgical texts.

The arguments and lobbying were vehemently pursued by the non conformists, but Charles would have non of it. His relationship with Roman Catholics in the end was unclear, his brother James who was to succeed him was a practising Catholic and it is believed that he was converted to Catholicism on his death bed, whether he was aware of the fact isn’t known.

This was the political environment that Francis and the Society of Friends or Quakers found themselves in. Quakers had no clergy, no pulpit, no ceremony, nor did they worship in a church. Quakers met in someone’s home or a simple meetinghouse. This was as far away from the requirements of the Book of Common Prayer as you could get.

Quakers were severely persecuted they could be fined, jailed, whipped even be subject to ‘tongue boring’.

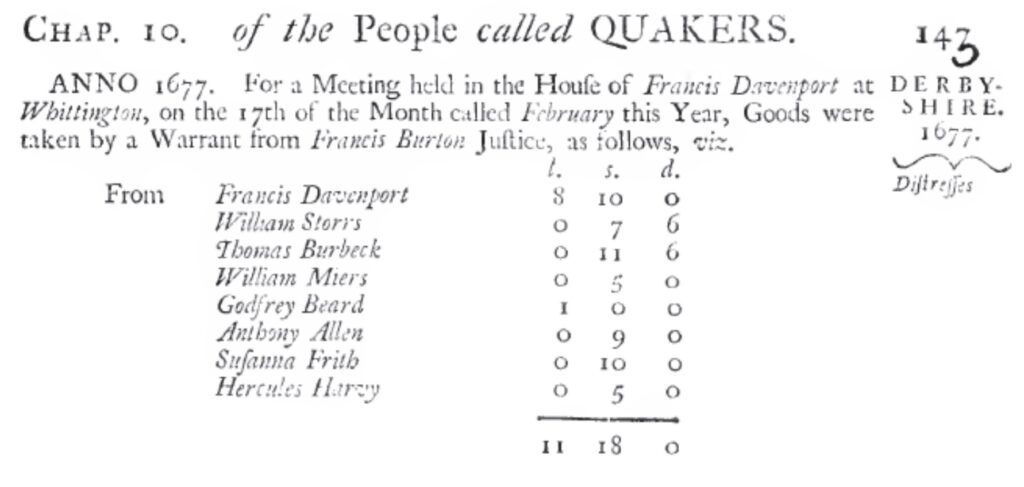

On 17th February 1677 Francis was holding a Quaker meeting in his home in Whittington when it was raided by officers of the Government. Francis and those attending the meeting were fined

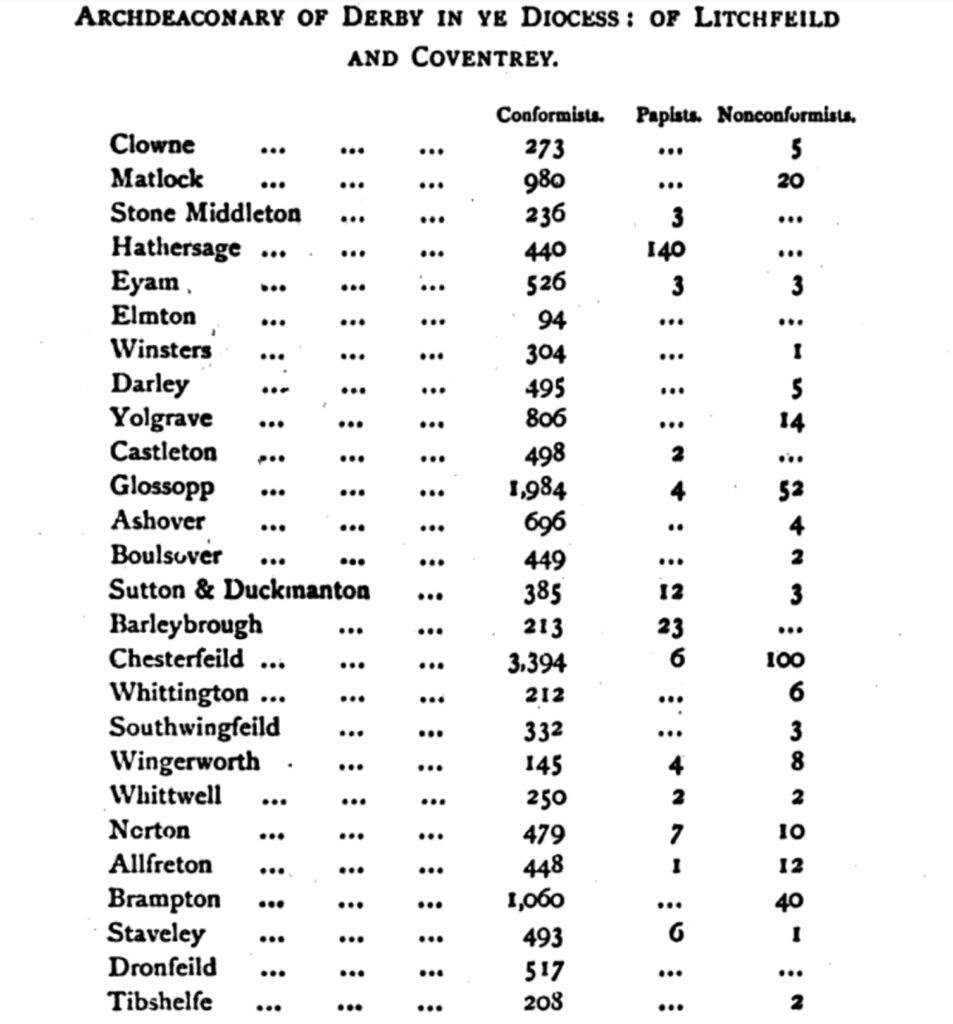

Also in 1677 the Bishops wanted an understanding of the numbers of those refusing to follow the requirements of the Book of Common Prayer. As part of the Visitation process (where a Bishop or their representative visited the parishes to check on clergy and their work in the parish) information was sought as to known conformists, papists and non conformists.

Some results from the Archdeaconry of Derby

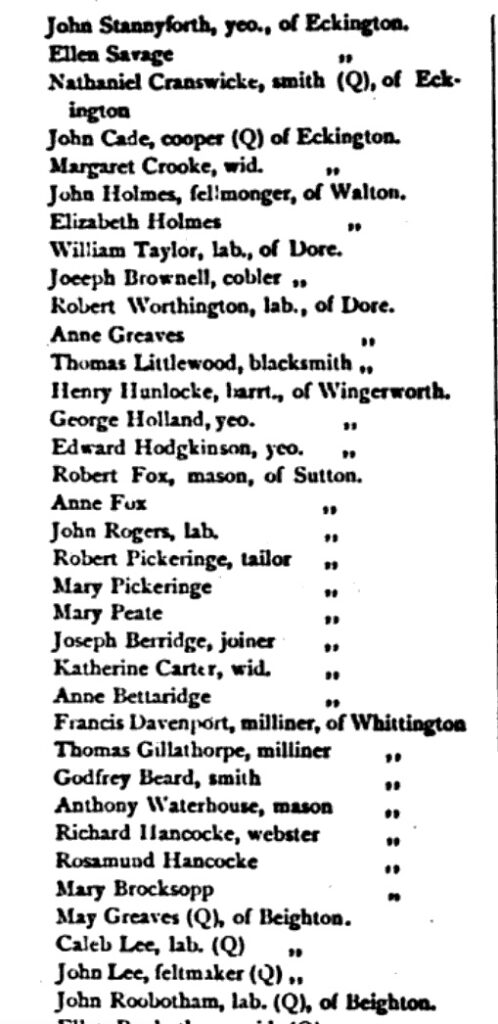

In 1682 an order was made in the Court of assizes for every known person who refused to attend the Sunday Church of England service be fined 12 pence each time they failed to attend. From this list we can see that Francis was listed as one of those subject to a fine

These 2 listings are from Rev.J Charles Cox book Three Centuries of Derbyshire Annals – Records of the Quarter Sessions of the County of Derby

Probably as a result of these pressures Francis decided to emigrate with his family to America. According to the History of Burlington and Mercer Counties, New Jersey. 1883

‘Francis Davenport, of Whittington, in Derbyshire, England, came to Burlington in 1683, with his wife, Sarah, and three daughters born at Whittington, Sarah, Anne, and Bridget. He located on a tract of seventy-seven acres of land on Crosswicks Creek, about three-quarters of a mile east of the village of Crosswicks. On it he built his cabin, not far from the third ford of the creek. Here he opened a store, receiving his goods by water from Burlington. We find in Revell’s “Book of Surveys,” page 90, 1st mo. 1691, “Surveyed there for Francis Davenport one parcell of land adjoining to his former settlement, containing seventy-seven acres, the two tracts contayning together 677 acres besides allowance for Highways at five acres per hundred.”

The village where Francis and his family settled was believed to be Recklesstown which had been named in honour of one of its founders, Joseph Reckless. However a local congressman (believed to be Francis) considered the name to be subject to ridicule and so on 6th November 1888 the community’s name was changed to Chesterfield, named, it was said, after the 2nd Earl of Chesterfield whose seat of Chesterfield was in Derbyshire, where many of the township’s earliest settlers had lived. The township was reformed by Royal charter on January 10, 1713, and was incorporated as one of New Jersey’s initial 104 townships by the Township Act of 1798‘

I am unable to trace the source but it was reported ‘FRANCIS DAVENPORT, however, was the original of the famous “Pooh Bah” of Gilbert and Sullivan’s opera, holding at one and the same time the offices of high sheriff of Burlington County, justice of the peace of Somerset, Essex, Bergen, Gloucester, Burlington, Salem, Cape May, Monmouth and Middlesex Counties. He was also an assemblyman at various times, and a judge of the higher courts, thus serving continuously in several important offices until his death.’

Francis’s occupation was listed as milliner.

As well as the 3 daughters that emigrated to America with Francis and Sarah they had another 7 children 2 of which sadly died in infancy. Sarah died in 1691.

Francis later married Rebecca (Whitton) Decow, widow, of Isaac Decow, of New Castle County, Pennsylvania in 1692.

Francis and Rebecca had 2 children Isaac and Rebecca.

Francis died on 1st February 1707 in Burlington, New Jersey.

Returning to the Monarchy’s relationship with the church Charles II was succeeded as we noted by his brother James who was to become James II of England and Ireland and James VII of Scotland. As already noted James was a practising Roman Catholic which did not meet the mood of the Country at the time.

In June 1688, two events turned dissent into a crisis; the first, on 10 June, was the birth of James’s son and heir James Francis Edward. This raised the prospect of initiating a Roman Catholic dynasty which meant excluding his Anglican daughter Mary and her Protestant husband William III of Orange. The second was the prosecution of the Seven Bishopsfor seditious libel; this was viewed as an assault on the Church of England and their acquittal on 30 June destroyed his political authority in England. The anti-Catholic riots in England and Scotland that ensued, led to a general feeling that only his removal from the throne could prevent a civil war.

This is where Whittington entered into history. It was here in 1688 that three conspirators met to plan what would become the Glorious Revolution, an invitation to William of Orange to take the throne of England in place of James II. The conspirators were moved to action by the events described above.

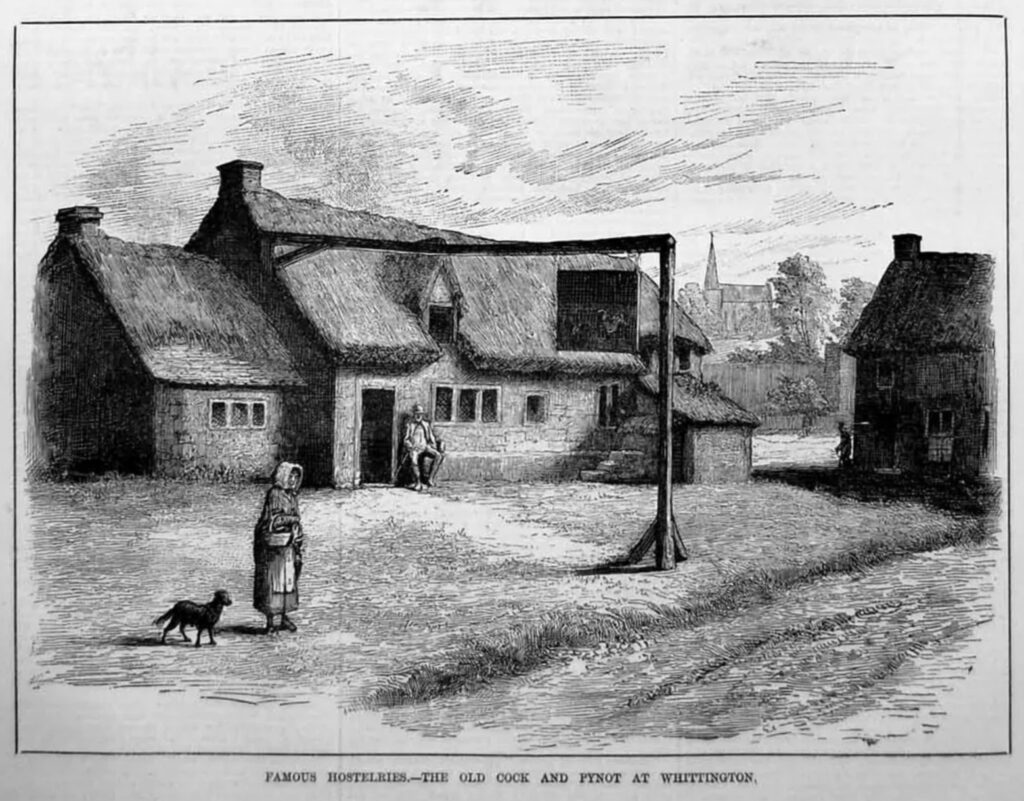

Three local nobles William Cavendish the 4th Earl of Devonshire, John Darcy the fourth son of the Earl of Holderness, and the Earl of Danby. Their meeting was ostensibly a hunting party, and was planned for Whittington Moor, but when the weather turned stormy, the three men sought refuge at the inn, known as the Cock and Pynot (‘pynot’ being a local term for a magpie). Together the three men composed a letter inviting Prince William to take the English throne, with his wife Mary.

Their plan was to conquer the north, then march south against James. The letter, written in code, recorded their plans and invited William to sail to England and take the crown. Though all three men helped prepare the plan, only the Earl of Devonshire signed it.

As history records, James fled at Prince William’s approach, and the so-called Glorious Revolution was a bloodless change of monarch. The Earl of Devonshire was rewarded for his role in the revolution with a dukedom, becoming the 1st Duke of Devonshire.

Prior to his arrival in England, the future king William III was not Anglican but a member of the Dutch Reformed Church. As a Calvinist and Presbyterian he was now in the unenviable position of being the head of the Church of England, while also being a Nonconformist. This was not his main motive for promoting religious toleration. More important in that respect was the need to keep happy his Roman Catholic allies, Spain and the Holy Roman Emperor, in the coming struggle with Louis XIV. Though he had promised legal toleration for Roman Catholics in his Declaration of October 1688, William failed in this respect, owing to opposition by the Tories in the new Parliament. The Revolution led to the Act of Toleration of 1689, which granted toleration to Nonconformist Protestants but not to Roman Catholics. Catholic emancipation would be delayed for 140 years.

Although most in Britain accepted William and Mary as sovereigns, a significant minority refused to acknowledge their claim to the throne, instead believing in the divine right of kings, which held that the monarch’s authority derived directly from God rather than being delegated to the monarch by Parliament. Over the next 57 years Jacobites pressed for restoration of James and his heirs. Nonjurors in England and Scotland, including over 400 clergy and several bishops of the Church of England and Scottish Episcopal Church as well as numerous laymen, refused to take oaths of allegiance to William.

The Nonjuring schism refers to a split in the established churches of England, Scotland and Ireland, following the deposition and exile of James II and VII in the 1688 Glorious Revolution. As a condition of office, clergy were required to swear allegiance to the ruling monarch; for various reasons, some refused to take the oath to his successors William III and II and Mary II. These individuals were referred to as Non-juring, from the Latin verb iūrō, or jūrō, meaning “to swear an oath”.

In the Church of England, an estimated 2% of priests refused to swear allegiance in 1689, including nine bishops. Ordinary clergy were allowed to keep their positions but after efforts to compromise failed, the six surviving bishops were removed in 1691. The schismatic Non-Juror Church was formed in 1693 when Bishop Lloyd appointed his own bishops. His action was opposed by the majority of English Non-Jurors, who remained within the Church of England and are sometimes referred to as “crypto-Non-Jurors”. Never large in numbers, the Non-Juror Church rapidly declined after 1715, although minor congregations remained in existence until the 1770s.